Letter to the Hebrews – Part One

Catholic letters

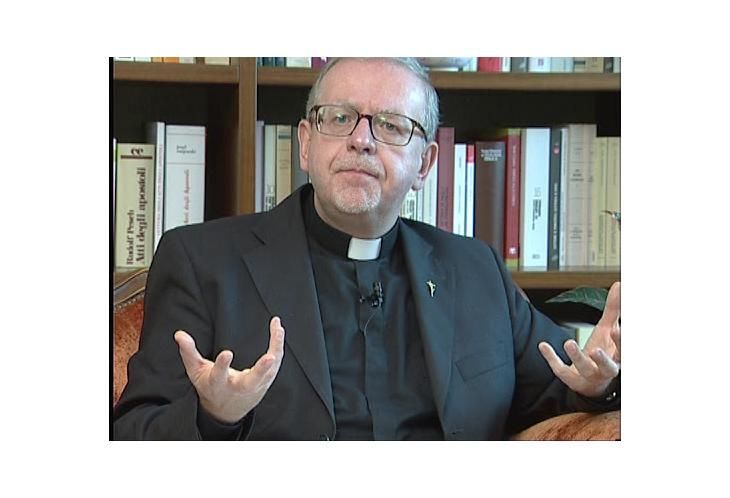

Videos from Fr Claudio Doglio

Original voice in italian, with subtitles in English, Spanish, Portuguese & Cantonese

Videos subtitled and voice over in the same languages are also available.

Letter to the Hebrews – Part One

The last letter in the collection of Paul's writings is the Letter to the Hebrews. It is a very special letter, very different from the others and very long, and yet it appears at the end. The person who compiled the collection of the New Testament, put together 14 writings related to Paul and arranged them in order of length, beginning with the letter to the Romans, which is the longest.

The letter to the Hebrews, which is as long as the first, why does he place it at the end of the collection? Because Paul's name does not appear in it and, likely, it is not a work of Paul, so much so that the liturgy itself has preserved the formula Letter to the Hebrews. My professor at the Bible school in Rome, who became a cardinal, Father Albert Vanhoye, when he started his course on Paul’s letters, he used to say ironically: "We are going to deal with the Letter of St. Paul to the Hebrews, which is not a letter, it is not from St. Paul, and not to the Hebrews". From this, we can understand the usefulness of the titles.

Let us reflect on these three elements: It is not a letter, so what is it? It's a theological homily, a kind of lecture delivered at an important and solemn moment with a theological reflection on the role of Jesus Christ. It is not by St. Paul but by someone linked to Paul's environment. One of the many names that have been used as the author is Barnabas and, according to my opinion, is the most likely of the many that are mentioned. Barnabas was not a disciple of Paul but a teacher of Paul; was the one who supported and introduced him. Barnabas was a Levite, therefore, a person trained in the liturgical mentality of the Old Testament priesthood.

Barnabas was a great preacher, so much so that he was given this nickname; his real name was Joseph, known as 'bar navah,' an Aramaic term meaning 'son of exhortation,' which in our language would correspond to a good preacher; and in fact, this work is defined as 'logos paracleseos,' that is, a discourse of exhortation. Not a letter but a discourse of exhortation, of encouragement, of instruction about Christ. Finally, it is not to the Hebrews, understood as a nation or an alternative community to the Christian community. The work is addressed to Christians, of whom many came from Judaism; therefore, Judeo-Christians, perhaps nostalgic for the solemnity of the Jerusalem temple and the rites of the ancient liturgy.

Faced with a community in crisis, the author reflects on the essential elements of the work of Christ, and wants to show how in the sacramental simplicity of the Christian liturgy is all perfect fulfillment of the history of salvation, much more than in the solemnity of the rites of the ancient temple of Jerusalem, which had much appearance but little substance.

This work was probably written in Rome, in the community of Rome in the '60s, when Paul was forced to stay there. It was probably Paul who, having found this text written by someone around him, as we have said perhaps Barnabas, approved it and had it copied and sent to the communities, so much so that in the final part, there is a kind of note added; we could speak of a note of recommendation with which Paul presented this text to his communities, recommending that they read it and distribute it.

The text does not begin as a letter, with the name of the sender, the name of the addressee, greetings and good wishes, but as a solemn discourse: " In times past, God spoke in partial and various ways to our ancestors through the prophets; 2 in these last days, he spoke to us through a son, whom he made heir of all things and through whom he created the universe.” The focus of this text is the work of Christ, the definitive word of God.

Having spoken many times and in many ways through the prophets, God has now spoken through his Son, and who is this Son? He is the one who has created the world; this Son "is the refulgence of his glory, the very imprint of his being, and who sustains all things by his mighty word.” These are very solemn qualifications of the role of Christ. The author is convinced of his divinity and speaks of him as a divine person, irradiation of the divine substance, a ray of the one light, the imprint of the divine substance.

This Son, "when he had accomplished purification from sins, he took his seat at the right hand of the Majesty on high, as far superior to the angels as the name he has inherited is more excellent than theirs.” So, we see that the beginning is a solemn prologue to a lecture on Christology, a scholarly treatise on the person of Christ, but what did the author have to say? Something new and very important because the central theme of the letter to the Hebrews is the priesthood of Christ.

No other text in the New Testament speaks of Christ as priest. It is a novelty, the fruit of a theological deepening; it is a maturation that the author, a great theologian, has carried out starting from the apostolic tradition. Let us try to follow his reasoning a little. The apostolic preaching presented Jesus as the Christ, the Son of God, the fulfillment of all salvation history. Everything that was anticipated in the Old Testament is fully realized in Jesus. For example, Jesus fulfills the expectations of messianic kingship, as Jesus is condemned as king, he is recognized as the king of the Jews; the title messiah is a qualification of the king.

To recognize Jesus as messiah means acknowledging that he is the legitimate king, the heir to the throne of David. Jesus was king differently, but he was king, therefore, the whole messianic royal tradition finds in Jesus its fulfillment. This is what they all said from the beginning. Another aspect: the prophets were bearers of God's word, people who spoke in God's name to make the Lord known. Jesus presented himself as the one who reveals God, the prophet par excellence; people recognized him as the great prophet to come. God has, at last, visited his people. Jesus is the word of God; he is the one who speaks of God and makes God known. Much more than the prophets, he says things definitely, clearly.

But there was another very important aspect in the Jewish tradition that was not considered by the first Christian preaching; it was the priesthood, the liturgy of the temple, the whole sacred world of worship. Jesus came into conflict with this reality during his earthly life and was in dispute with the priestly temple class; and it was precisely the high priests of Jerusalem who organized to eliminate him and put pressure on Pilate to condemn him to death.

When we speak of the priesthood, we must be cautious to distinguish what was the Jewish mentality of the Old Testament from what is our Christian concept of priesthood. Therefore, I am speaking of the ancient mentality of the priesthood, with which the author of the letter to the Hebrews compares himself, because only by this reasoning will our Christian concept of the priesthood be born. We will talk about it at the end; now, let us look at the biblical mentality.

The priestly task in the biblical tradition is entrusted to a family, exclusively to a group of persons linked to a single family, the family of Levi, particularly the house of Aaron, even more particularly, to the descendants of Zadok. Therefore, a small group belonging to a closed caste. In the biblical mentality, one is born a priest; one is a priest because he belongs to a priestly family. If you don't belong to a priestly family, nothing can be done. You cannot be a priest, is an exclusive task of the Levites.

Jesus belonged to the tribe of Judah; linked to the family of David he belongs to the tribe of Judah, which is another tribe compared to the tribe of Levi. Of the tribe of Judah no one ever exercised priestly functions, therefore, Jesus as a historical man did not belong to the priestly caste and according to the ancient criteria he never became a priest, i.e., he never performed sacrificial rites inside the temple in Jerusalem because it was an activity exclusively reserved for the Levites. Jesus always remained outside the gate that separated Israel from the priestly group. In fact, in the Gospels, there is no episode in which Jesus officiated a priestly rite.

So, if this is so, Jesus was not a priest; he didn't do anything priestly; therefore, all that liturgical world spoken of in the Old Testament has not found fulfillment in him and is discarded; it is lost. It was the prophetic word of God, but it was not fulfilled in Jesus. Our author must have asked himself this question and earnestly sought an answer. His demonstrative theological answer is outlined in the letter to the Hebrews in which the author affirms that Jesus is a priest but differently, as he was a king differently, as he was a prophet differently, he is also a priest but in a different way. It is not enough to say it; it must be demonstrated.

The author presents it according to the theological criteria of his time and of the Jewish environment. That is to say, he goes looking for biblical documentation. The author found the biblical proof in Psalm 110; is a very important text that we continue to use on the eve of every Sunday of the year, it is the first psalm of festive vespers: The LORD says to my lord: “Sit at my right hand, while I make your enemies your footstool.” The first verse speaks of the enthronement of the messiah who sits on the throne at the right hand of God. The early apostolic community used this verse to say that Jesus is king, that Jesus is the messiah, that at the resurrection, he sat down at the right hand of the Father. We keep repeating it also in the Creed. A little further on, in verse 4, the same Psalm 110 says: The LORD has sworn and will not waver: “You are a priest forever in the manner of Melchizedek.”

This verse had not been considered, and our author made this reasoning: If the first verse applies to the resurrected Christ, we must also apply verse 4. He who is the messiah king who sits at the right hand of the Father is also a priest forever after the manner of Melchizedek. This is the point: the resurrected Christ became a priest, but not after the order of Levi, of Aaron, of Zadok, that structure that supported the temple in Jerusalem, but according to the order of Melchizedek, an ancient and strange character used to indicate a priesthood different from the Levitical.

When the author found this demonstrative element in the Scriptures, he was convinced of his choice and he began to elaborate a great discourse and constructed this Christological homily to explain in what sense Jesus is a priest. The starting point of this observation is the fact that Christ is now risen, alive, in the presence of God and seated at the right hand of the Father. The author is not thinking of the ancient historical phase of Jesus' earthly life but about his present condition.

What is Jesus doing now in the glory of the Father? He is interceding for us, but this is precisely the priestly task; what should the priest do according to the biblical teaching? To be a mediator between God and people. and between people and God, but the true mediator, the only one who could really perform a mediation is Jesus Christ. Since he is resurrected and present in the glory of God, and since God became human, he is the perfect mediator. Therefore, the resurrected Christ is the mediator, who is always alive to intercede for us.

In this sense, the letter to the Hebrews firmly holds that Jesus is a priest. And so, it completes the picture: in him, every expectation of the Old Testament has been fulfilled, even all the liturgical cultic traditions of sacrifice have been fulfilled in the priesthood of Christ.