The Gospel

according to Matthew

Part 11. The Parables of Fidelity

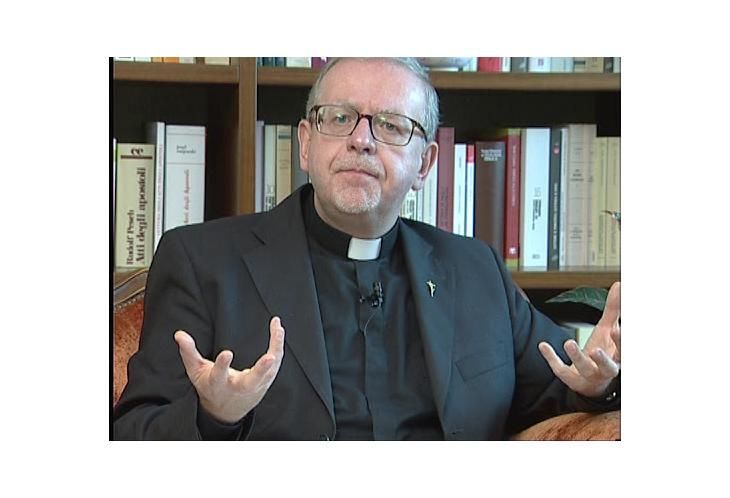

Videos from Fr Claudio Doglio

Original voice in italian, with subtitles in English, Spanish, Portuguese & Cantonese

Videos subtitled and voice over in the same languages are also available.

11. The Parables of Fidelity

The last encounters of Jesus during his stay in Jerusalem, on the temple esplanade, turn into confrontations. All evangelists present this situation of rupture that marked the end of Jesus' life. In particular, Matthew gives specific emphasis to this contrast, perhaps because the school of Matthew, which was then working towards the 80s in a context of strong controversy with the new synagogue, reorganized by Johanan) ben Zakkai, was in controversy with the reformed Jewish structure that tried to preserve its Jewish identity after the destruction of the temple, and was, therefore, closed and opposed to the Christian group. They had expelled those who recognized Jesus as the Messiah; began an authentic confrontation with heavy situations of verbal controversy and, perhaps, also opposition with painful consequences for Christians because they found themselves in a minority position without civil rights and protection.

And the 23rd chapter of the gospel according to Matthew maintains this tone of strong controversy. The last great discourse begins, the eschatological one, the final one, which analyzes the definitive fulfillment of history and occupies chapters 23, 24 and 25; and corresponds to the first great discourse of the Gospel according to Matthew, the programmatic one that includes chapters 5, 6 and 7, generally known as the ‘mountain discourse.’ The eschatological discourse, which is properly contained in chapter 24, has a preamble in chapter 23 and a parabolic appendix in chapter 25.

Chapter 23 contains strong and great reproaches that Jesus addresses to the scribes and Pharisees. We found a collection of "Woes!" which is the reverse of the beatitudes. As the Sermon on the Mount opens with congratulations to those who welcome the kingdom of God, so the final and definitive discourse opens showing the ruin of those who reject this word and this reception.

Chapter 24 contains an ancient formulation of the early Christian community, in apocalyptic language, that is, the end is announced; it is not easy to understand in what sense the end is spoken of. First of all, the first objective is to announce the end of Jesus, which is his dramatic passion and death. It is the drama of rejection that leads to ruin, to the destruction of his life. The apocalyptic announcement is typically Easter; it is the inversion of destiny. The one who was killed returns victorious on the clouds of heaven. It is the announcement of the death and resurrection of Jesus as a turning point in history made by God. The stone discarded by the builders has become the cornerstone. God made this wonder.

The other final perspective refers to the city of Jerusalem. In the year 70, in fact, the Roman armies conquered the city and destroyed it. It was a decidedly painful end for the Jewish community that lost the temple and the entire liturgy related to the temple. The year 70 caused a radical change. And a group from the synagogue, from a Pharisee school, organized the reform and tried to survive this disaster. Somehow, the primitive Christian community saw in this eschatological discourse the announcement of the ‘eschaton,’ the end of Jerusalem, of that structure, of the temple destined to end.

But, deep down, against these two events that happened, the death of Jesus and the end of the temple, there is also the universal perspective of the end of the world, the final fulfillment. It is not a text offering indications of when it will happen, but rather it indicates that history is moving towards its fulfillment, which can be tragic, precisely in light of the two tragedies that have already occurred: the murder of the Messiah and the destruction of the holy city.

To this ancient apocalyptic text, preserved almost the same in Mark and Luke, Matthew added another chapter, which is the 25th, with three parables of his own. As he did with the three parables of the rejection of Israel, now he proposes three parables about faithful commitment; and also in this case Matthew has a vision on the history of salvation. The three parables do not say the same thing, but target different situations in the story. They are the parable of the ten girls who go to meet the husband of the servants who are entrusted with the talents of the master. This is the so-called universal judgment, when the Lord will gather all the peoples and separate, like a shepherd, the sheep from goats. Let’s quickly see each of these parables.

The first takes place in a typically Palestinian context, in a town celebrating a wedding feast. Although it refers to local customs and traditions, there is not a very strong narrative coherence and the text is presented rather as an allegory, a metaphorical rereading of the history of salvation with the image of love, a nuptial meeting, the meeting of the bridegroom with the bride, an important Christological image. The husband is expected; it means that he is not there yet. The ten virgins who go out to meet the bridegroom are divided into two groups. This is what the narrator says, but it is not immediately understood. Five are wise and five are foolish (I would say, in a more common language, stupid). Do you understand who are the wise and who are the foolish?

There and then all ten are waiting for the bridegroom and they have torches, they must feed these torches with fuel oil so that they can continue to keep the flame alive. The bridegroom delays; it is late at night. They have fallen asleep. When it is the right moment when the bridegroom arrives, only 5 are prepared, the others are not prepared because they have no more oil and their torches are extinguished. They are not ready to welcome the bridegroom who comes. They are so foolish that they go looking for oil sellers at midnight and, naturally, find everything closed. And when they come back, the door is closed. They stay outside and knock, saying: ‘Sir, sir, open the door for us,’ but from within the bridegroom says: ‘I don’t know you.’ "Therefore, be vigilant, because you do not know the day or the hour."

This parable takes up the outline of the parable that closes the discourse on the mountain: "The wise man builds on rock and the foolish man builds on sand." A little earlier, in the discourse on the mountain, Jesus said: “Not those who says ‘Lord, Lord’ will enter the kingdom of heaven, but whoever does the will of my Father.” Here, in this parable, the stupid women knock saying, 'Sir, sir', but they don't go in because they didn't do the will of the Father. This is the key of the parable. What does the oil represent?

Personal commitment, the existential response of each one; this is not communicable, it is not simply transmitting from one to another. The wise man cannot transmit his oil to others because it is the commitment that has failed, and they personally have not joined. It is understood that they are stupid at the decisive moment, when it is too late, it is necessary to have thought about it before. The objective of eschatological discourse is precisely this: to think first.

The other parable, about the talents, presents rather an economic question, an administration with banks included. A rich gentleman entrusts his assets to his administrators and sets out on a journey. To one he entrusts five talents, to another, two, to another, one. Talent, in ancient language, is a unit of weight and is a way to quantify silver. A talent fluctuates between 40-60-100 kg, depending on the places. The word 'talent' should sound to us like kilos, ton.

The man entrusts one of his administrators with 5 tons of silver; and to the one who entrusts little, he gives 1 ton. It is not a small thing, it is not a coin to keep in your pocket; it is a ton of coins, therefore, a heritage that must be made to bear fruit. A widespread misunderstanding derives from the fact that in our language the word ‘talent’ has come to mean ability, quality, natural gifts, and the talents that the Lord gives us, we identify them as our gifts, our qualities and everyone must be said to exercise the gifts he received from the Lord. In fact, in the parable, it is said that the Master distributes his patrimony in a different way, giving to each according to his ability.

Therefore, talents are not skills. Talents are the patrimony left by the Lord. How could we then explain what the Lord left to his disciples? What is his heritage? —the gospel, grace, the Church, the sacraments, the word of God, exemplified in many ways. This is the wealth that has been given to us, it is the deposit, it is what is in the tradition of the pastoral letters called the ‘good deposit’, the deposit of faith. ‘Deposit’ is a banking term that closely recalls the imagery of this parable.

The first two administrators received a large deposit in the bank and they seek to make it produce more. When the owner returns, after a long time, they will return the capital with interest. That deposit has doubled the initial capital; instead, the third did nothing, he took that heritage and buried it; it was useless to him. When the owner returns, the man gives back to the owner what he received as it was, saying: “It was useless. I didn’t do anything about it.”

We understand that the drama is of someone who tells the Lord that the fact of having known the gospel was of no use to him. The fact that the Church has the sacraments, grace, the word of God "didn't help me at all." ‘My neighbor, an atheist, or of another religion, lived exactly like me, who had all this inheritance.' It is logical that the Lord reacts by saying: “Woe to you, wicked and lazy servant, you knew that I reap where I did not sow and gather where I did not scatter, you should have entrusted my money to the bankers so that on my return I would have withdrawn it with interest. Therefore, take away the talent from him and give it to the one with ten talents.” The servant who has done nothing is called wicked and lazy.

The old translation it had the term 'negligent,' a term that means 'lazy.' ‘Evil’ is synonymous with ‘lazy’; it is a parable addressed to Christians, to those in the Christian community who have received the patrimony of Christ, his deposit of faith and it is for them to use. Two actually use it; two-thirds use them well; some more, some less, the one with five talents also had more ability; received a lot and doubled it. The one who received a little less means that he had less capacity, but he also doubled it. This means that the commitment he has put has served him; the evangelical heritage has borne fruit, “Very well, good and faithful servant, you have been faithful in the little, I will give you authority over a lot. Enter your lord's feast.”

It is the announcement of joy for Christian administrators, for those in the Christian community who have an important role in the management of the evangelical heritage. ‘Faithful’ is the opposite of ‘lazy’. He who is lazy is not faithful. Not using the talents is treason; not making the gospel known is to betray the task the Lord has given you. We can see a small distinction between the first and the second parable. In the girls waiting for the bridegroom we can recognize the situation that precedes Christ; we can see in those young women the image of Israel waiting for the Messiah. When the Messiah arrives, some are ready and will receive him; while others are satisfied with the theory, but, in fact, they miss the opportunity and they do not enter the kingdom.

Instead, the parable of the administrators is addressed rather to the leaders of the Christian community, to those who come after Jesus, those who inherited his patrimony and it is up to them to make it work. Within this community, there are wicked and lazy people, like the one who entered the wedding banquet without the proper dress and is thrown out. Thus, this unworthy and lazy administrator is expelled: “Cast him out into the darkness outside. There will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.”

The last scene, the one we call the universal judgment, looks like a universal opening where the people questioned are neither in the Israeli tradition nor in the Christian environment, but are people in general. In fact, in front of the Messiah, everyone is amazed. The king who sits on the throne says: “You have given me something to eat” – “You have not given me something to eat”, But both react by saying: "When did we see you hungry?" ‘We never knew when we fed you or not fed you.’

They don't know him, they don't know Jesus directly, but the revelation is: 'What you did or didn't do with the smallest of my brothers and sisters, you have done it or not done it to me.’ It is the revelation that the Messiah has as all people as brothers and sisters. The attitude that each one has towards others is the way to relate to the Messiah. Treating another person well is treating the Messiah well. To despise another person is to despise the Messiah. It is the criterion of judgment that is applied to those who have not received the patrimony of the gospel; that they do not have the expectation of the spouse, and have lived in a good or bad way; and the criteria is precisely that of the works of mercy, the welcoming, the service of the other.

Chapter 26 begins with the typical concluding formula: “When he finished this discourse, Jesus said to his disciples: You know that in two days Easter will be celebrated.” All these discourses are now over. With the fifth discourse the central part of the gospel ends and the last section follows, which narrates the passion, death, and resurrection of the Messiah.