The Gospel

according to Matthew

Part 12. Passion, Death and Resurrection according to Matthew

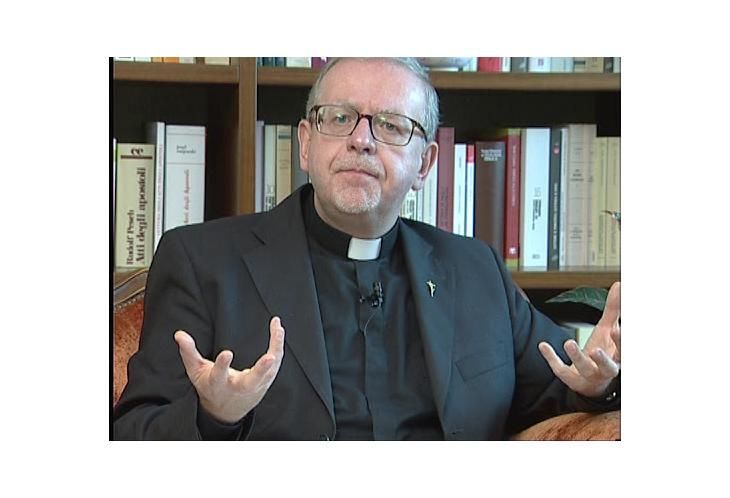

Videos from Fr Claudio Doglio

Original voice in italian, with subtitles in English, Spanish, Portuguese & Cantonese

Videos subtitled and voice over in the same languages are also available.

12. Passion, Death and Resurrection according to Matthew

The vertex of each gospel tells about the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus, so also the evangelist Matthew places the decisive events at the top of his narrative. The story of the passion is told in the four gospels, in two chapters. They usually correspond in all four narrations because the passion story was inevitably the first story to be formed. It is the basis of apostolic preaching.

The announcement of the resurrection of Christ led to the narration of how he died, why he died, how the decisive events of his existence went. Therefore, we find the same story, however conspicuously mediated in four different ways; each evangelist has given his own touch to this story. Mark highlights, above all, the impact of the events, the drama of rapidly unfolding events. Luke gives a sweet pedagogical tone to the events showing the innocent who is not abandoned neither by people nor by the Father; the good attitude of Jesus who looks, converts Peter; the word of forgiveness for those who kill him. John delves into the theological path and presents the glory of the cross, the raising of the king to the throne from where he draws everyone to himself.

Matthew respects the traditional canvas in the vast majority of cases, with some of its particular nuances from a more catechetical tone, where in some cases he intervenes precisely to show the meaning of the events. We notice this catechetical nuance of Matthew, particularly in the episode of the arrest of Jesus, when the disciple draws his sword to strike those who come to arrest the Master. Jesus told him, “Put your sword back in its place,” and adds a proverb, "All those who take the sword will die of the sword." It is not with violence that you respond to violence; it is not the way of Jesus: ‘Do not oppose the wicked’ he had said in the discourse on the mountain.

Now, Jesus applies this style concretely and still specifies: “Do you still believe that I cannot pray to my Father who would immediately put more than twelve legions of angels at my disposal?” If he wanted to oppose he would have twelve legions of angels available, other than twelve disciples, one of whom is a traitor. ‘I could but I don’t want, I don’t use force. I do not choose these supernatural methods, but I abandon myself to violence and I give in to fulfill God’s plan. If I oppose myself with violence or using angels, how would the Scriptures be fulfilled?’, according to which this is the way of God must be, of humility and passion, of responding to evil with good, with meekness, and this is the way in which Jesus reverses the situation and saves humanity.

This discourse in that tragic moment is a typical element of Matthew. It is a kind of catechetical synthesis in which the evangelist puts into Jesus’ mouth the call to the fundamental elements of his catechesis.

Another typical aspect of Matthew is the insistence on the role of Judas. It is only Matthew who narrates, among other things, the reaction of Judas after seeing Jesus condemned and the tragedy of his suicide. We do not take this role of Judas too easily for granted. Many times there has been talk of a tragic role of a predestined man as if Judas must necessarily do what was necessary for God’s plan to be fulfilled. It is absolutely not true.

Jesus was not a fugitive hidden who knows where, nowhere to be found. He was in the temple every day, therefore, if we reason, we see that the role of Judas was minimal, it was not essential in order to arrest Jesus; it was just convenient for the temple authorities to arrest Jesus in secret, when no one saw them. Apprehending him on the temple esplanade would probably have caused a riot of the people and some disturbances. Judas has not betrayed Jesus for economic reasons; it is not the desire for money that prompted him. They promise him 30 denarii.

The denarius is generally evaluated as the wage of a worker per day, therefore, thirty denarii correspond to an average monthly salary that today we could qualify thirty denarii with about $500. A friend is not betrayed by such a sum. What reason does Judas have that he should hand over Jesus over a small amount of money? There is probably something else behind it. Judas follows Jesus, he is linked to Jesus, he is his disciple. In fact, the verb used in the Greek text is not the verb ‘to betray’ but ‘to hand over’. Judas is not the traitor, but the one who delivers Jesus. It sounds very different.

It is that we are accustomed to the verb 'betray,' and we have also been betrayed in understanding. The Greek verb ‘para dídomi’ translates in Latin as ‘contract’ = ‘tradere.’ which gives rise to the English language of commerce, ‘to trade’. ‘Tradere’ is transmission, the delivery from one to the other. Why did Judas surrender Jesus? We have no precise indications. We can only imagine it, but the most likely thing is that Jesus was too slow, too mild, too weak for Judas. Judas must have wanted to force time. He thought that Jesus does not reveal himself… ‘he does not make himself known… he does not oppose… forcefully, you have to push him to make him say who he really is, in such a way that the authorities recognize him, agree and proceed to the work of liberation.’

Judas probably thought that he was helping God’s plan by doing it his way. He did it for a good purpose, he delivered Jesus in such a way that he had the possibility to speak face to face with the highest authorities of Israel. Surely, they would understand each other, they would agree and the great work of liberation would finally begin. When Judas realizes that Jesus has not revealed himself, has not agreed and has been condemned, even taken to Pilate to be sentenced to death, he was saddened… saddened as he was the one who had handed him over, and “seeing that Jesus has been condemned, taken by remorse, he returned the thirty silver coins to the chief priests and elders, saying, ‘I have sinned by delivering an innocent man to death.’ They replied: ‘What about us? That is your problem.’”

This report is a typical item from Matthew. The reaction of the priestly authorities of the temple shows spiritual narrow-mindedness. They have gotten what they were looking for. They have used Judas to strike without getting noticed. The problems of conscience are Judas’. The authorities just do not care, as it telling Judas: ‘Do what you want now; fix it as you want.' They kick him out, they've used him and now they throw him away. Poor Judas, when he sees that things do not go according to what he thought, he repents. He let himself be taken by remorse and admits that he has sinned, “I have handed innocent blood into your hands,” that is, ‘an innocent person whom you have condemned to death, of which you will shed blood. I have the responsibility, but I didn’t want that.’

Judas is a disciple who wants to do his own thing, who follows Jesus but does not listen and would like to teach him to be the messiah and imposes something on him; and discovers the drama of being responsible, but he did not want to be ... Judas' worst mistake was not trusting in God's mercy. "He threw the money into the sanctuary, left and hanged himself." This is the drama of not trusting in mercy and, in any case, we have no possibility of affirming that even Judas was condemned. He may have accepted God's mercy and opened up.

It is the drama of a stubborn disciple, very similar to us. Judas' betrayal is very similar to the betrayal of many Christians who follow Jesus, but want to make him do what they have in mind and for a good purpose, according to their schemes, to their tastes, unfortunately, they want to dominate and bend him. This attempt is always dramatic and unsuccessful. Jesus is condemned by Pilate, carried to the place of execution, hang on the cross, outraged and ridiculed by the people present, ends his life with a loud cry: "Elí Elí lema sabactani."

Thus, Matthew mentions the beginning of Psalm 21 in Hebrew. It marks the beginning of an important biblical prayer. If we do not take into account that it is a psalm, a long psalm with many themes, we run the risk of reading in this word of Jesus, as almost despair: "My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?" And it is then possible to reflect on the sense of abandonment and on the theological problem: How God can be abandoned by God. But it does not seem to me the best way to follow and understand the text.

If we go and reread the entire psalm, we realize that it is a very beautiful prayer of great trust. Not only that, but, in the second part of the psalm, it is, the announcement of life, the fulfillment that the Lord has offered to his servant, the guarantee that he will live and have an offspring. It is a prayer of trust.

Quoting the first verse helps the evangelist to say that Jesus prayed with the words of the psalms, particularly with that psalm. From that text, Jesus took verses for his prayer. Jesus prayed with the psalms until the last moment of his life. His prayer is made up of verses taken from the psalms. The last cry is an affirmation of trust that burns within this psalm.

There is a particular verse in which it is said: "From my mother's womb, you are my God." In Hebrew: "Eli atá." "Some of those present, upon hearing him, commented: He is calling Elijah." ‘Elí = my God” -- “Atá = you” = ‘You are my God…”. It is the final cry of Jesus. A cry of great confidence, of abandonment: "In spite of everything, You are my God."

But an Aramaic ear could have understood the word slightly differently. They could have heard: 'Eli√° ta'. The same phrase, heard, if written in Aramaic means: "Elijah, come." That is why: "Some of those present, upon hearing him, commented: He is calling for Elijah." “Immediately one of them ran, took a sponge soaked in vinegar and gave him a drink with a cane. The others said: Wait, let's see if Elijah comes to save him.” Elijah does not come ... It is the final misunderstanding. Jesus was not calling Elijah. Jesus trusted his God, put his life in the hands of the Father.

The death of Jesus is accompanied by apocalyptic phenomena. They all point out that the veil of the temple was torn, the earth shook, the rocks broke. Matthew adds: the earthquake, the rocks that break, the sepulchers that open are eschatological signs. Is it the end of the world? Yes, it is the end of a world with the death of Jesus; there is an end, there is a fulfillment, there is a reversal of the situation, especially that earthquake that opens the tombs, it is the apocalyptic image of the catastrophe.

The word ‘catastrophe’ in Greek means this gesture that we make accompanying the idea of change. Things have changed 'from like this - to like this.' A catastrophe is to turn what is below and put it on top. It is the reversal of destiny. The earthquake is a very frequent apocalyptic symbol to indicate the intervention of God. Things are upset. They are no longer the same. It is the structure of the world that is upset. But since the structure was negative and corrupt, reversal means correction and salvation. It is the same image of the earthquake that the evangelist Matthew takes at the time of the resurrection.

Let's not forget that the evangelists do not recount the resurrection, but the visit of the women and the disciples to the empty tomb. They tell the experience of the empty tomb and the encounter with the Risen One, but not the moment of the resurrection. At the beginning of chapter 28, the last of his gospel, Matthew writes: “In the end of the Sabbath, as it began to dawn toward the first day of the week, came Mary Magdalene and the other Mary to see the sepulcher. And, behold, there was a great earthquake: for the angel of the Lord descended from heaven, and came and rolled back the stone from the door, and sat upon it. His countenance was like lightning, and his raiment white as snow.” It is an apocalyptic description. The angel is like lightning that shakes the earth. It is the description that only Matthew presents to explain the event that it was God who intervened and reversed the situation from above.

The great earthquake characterizes the reversal of the situation. The angel of the Lord rolls the stone. It is the image of evil; it is death. It is that stone placed on top, which hides everything they put into it to mean that something is dead and buried, everything is finished. But instead, the lightning from heaven shakes the earth, moves the stone and the victorious angel sits on it; he sits on the symbol of death. And the Risen Christ meets the women and the disciples and sends them all over the world.

We have come to fulfillment. “I have been given full authority in heaven and on earth. Go and make disciples among all the peoples.” The beginning of the church’s mission is the end of the gospel. We started from this ending because everything starts from here. With the experience of the risen Christ, the disciples, and Matthew among them, went back to the beginning and remembered what happened and they told us about it so that we too become his disciples.

Listening to the Gospel, understanding it well helps us each time to grow in this dimension of disciples. We are called to learn from Jesus, to learn from Jesus in person, to truly become his disciples. I sincerely hope that listening to these words and reading these texts will really help us to become disciples of Jesus.